United States v. O’Brien

391 U.S. 367 (1968)

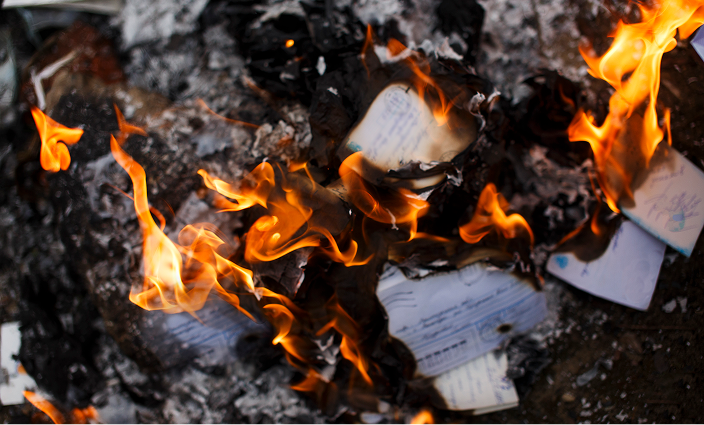

On March 31, 1966, David Paul O’Brien and three others burned their draft cards on the steps of a South Boston courthouse. A sizable, hostile crowd gathered. Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation took the four into the courthouse to protect them and to question them. The agents told O’Brien that he had violated a 1965 amendment to the Selective Service Act of 1948 that made it illegal to “destroy or mutilate” draft cards (formally known as registration and classification certificates, two small white cards issued when someone registers with the local draft board).

O’Brien replied that he understood but had burned his card anyway because he was “a pacifist and as such [could not] kill.” O’Brien was convicted and received a sentence of up to six years. A federal appeals court, however, reversed the conviction, finding that O’Brien’s expressive actions were protected by the First Amendment. The United States asked the Supreme Court to hear the case.

Mr. Chief Justice Warren delivered the opinion of the Court.

O’Brien … argues that the 1965 Amendment is unconstitutional as applied to him because his act of burning his registration certificate was protected “symbolic speech” within the First Amendment. His argument is that the freedom of expression which the First Amendment guarantees includes all modes of “communication of ideas by conduct,” and that his conduct is within this definition because he did it in “demonstration against the war and against the draft.”

We cannot accept the view that an apparently limitless variety of conduct can be labeled “speech” whenever the person engaging in the conduct intends thereby to express an idea. However, even on the assumption that the alleged communicative element in O’Brien’s conduct is sufficient to bring into play the First Amendment, it does not necessarily follow that the destruction of a registration certificate is constitutionally protected activity. [W]hen “speech” and “nonspeech” elements are combined in the same course of conduct, a sufficiently important governmental interest in regulating the nonspeech element can justify incidental limitations on First Amendment freedoms. To characterize the quality of the governmental interest which must appear, the Court has employed a variety of descriptive terms: compelling; substantial; subordinating; paramount; cogent; strong. Whatever imprecision inheres in these terms, we think it clear that a government regulation is sufficiently justified if it is within the constitutional power of the Government; if it furthers an important or substantial governmental interest; if the governmental interest is unrelated to the suppression of free expression; and if the incidental restriction on alleged First Amendment freedoms is no greater than is essential to the furtherance of that interest. We find that the 1965 Amendment to §12(b)(3) of the Universal Military Training and Service Act meets all of these requirements, and consequently that O’Brien can be constitutionally convicted for violating it.

The constitutional power of Congress to raise and support armies and to make all laws necessary and proper to that end is broad and sweeping. The power of Congress to classify and conscript manpower for military service is “beyond question.” Pursuant to this power, Congress may establish a system of registration for individuals liable for training and service, and may require such individuals within reason to cooperate in the registration system. The issuance of certificates indicating the registration and eligibility classification of individuals is a legitimate and substantial administrative aid in the functioning of this system. And legislation to insure the continuing availability of issued certificates serves a legitimate and substantial purpose in the system’s administration.

O’Brien’s argument to the contrary is necessarily premised upon his unrealistic characterization of Selective Service certificates. He essentially adopts the position that such certificates are so many pieces of paper designed to notify registrants of their registration or classification, to be retained or tossed in the wastebasket according to the convenience or taste of the registrant. Once the registrant has received notification, according to this view, there is no reason for him to retain the certificates. O’Brien notes that most of the information on a registration certificate serves no notification purpose at all; the registrant hardly needs to be told his address and physical characteristics. We agree that the registration certificate contains much information of which the registrant needs no notification. This circumstance, however, does not lead to the conclusion that the certificate serves no purpose, but that, like the classification certificate, it serves purposes in addition to initial notification. Many of these purposes would be defeated by the certificates’ destruction or mutilation. Among these are:

- The registration certificate serves as proof that the individual described thereon has registered for the draft. [I]n a time of national crisis, reasonable availability to each registrant of the two small cards assures a rapid and uncomplicated means for determining his fitness for immediate induction, no matter how distant in our mobile society he may be from his local board.

- The information supplied on the certificates facilitates communication between registrants and local boards, simplifying the system and benefiting all concerned. To begin with, each certificate bears the address of the registrant’s local board, an item unlikely to be committed to memory. Further, each card bears the registrant’s Selective Service number, and a registrant who has his number readily available so that he can communicate it to his local board can make simpler the board’s task in locating his file. …

- Both certificates carry continual reminders that the registrant must notify his local board of any change of address, and other specified changes in his status. The smooth functioning of the system requires that local boards be continually aware of the status and whereabouts of registrants, and the destruction of certificates deprives the system of a potentially useful notice device.

- The regulatory scheme involving Selective Service certificates includes clearly valid prohibitions against the alteration, forgery, or similar deceptive misuse of certificates. The destruction or mutilation of certificates obviously increases the difficulty of detecting and tracing abuses such as these. Further, a mutilated certificate might itself be used for deceptive purposes.

The many functions performed by Selective Service certificates establish beyond doubt that Congress has a legitimate and substantial interest in preventing their wanton and unrestrained destruction and assuring their continuing availability by punishing people who knowingly and willfully destroy or mutilate them. …

We think it apparent that the continuing availability to each registrant of his Selective Service certificates substantially furthers the smooth and proper functioning of the system that Congress has established to raise armies. We think it also apparent that the Nation has a vital interest in having a system for raising armies that functions with maximum efficiency and is capable of easily and quickly responding to continually changing circumstances. For these reasons, the Government has a substantial interest in assuring the continuing availability of issued Selective Service certificates.

It is equally clear that the 1965 Amendment specifically protects this substantial government interest. We perceive no alternative means that would more precisely and narrowly assure the continuing availability of issued Selective Service certificates than a law which prohibits their willful mutilation or destruction. The 1965 Amendment prohibits such conduct and does nothing more. In other words, both the governmental interest and the operation of the 1965 Amendment are limited to the noncommunicative aspect of O’Brien’s conduct. The governmental interest and the scope of the 1965 Amendment are limited to preventing harm to the smooth and efficient functioning of the Selective Service System. When O’Brien deliberately rendered unavailable his registration certificate, he willfully frustrated this governmental interest. For this noncommunicative impact of his conduct, and for nothing else, he was convicted. …

In conclusion, we find that because of the Government’s substantial interest in assuring the continuing availability of issued Selective Service certificates, because the [1965 Amendment] is an appropriately narrow means of protecting this interest and condemns only the independent noncommunicative impact of conduct within its reach, and because the noncommunicative impact of O’Brien’s act of burning his registration certificate frustrated the Government’s interest, a sufficient governmental interest has been shown to justify O’Brien’s conviction.